Pre-war diary of HSH Ashmead-Bartlett

Thursday 25th January 1911 – a debating class and a workhouse

This morning I went with Irene to Madame D’Estesse’s debating class. It takes place in the upstairs room of a house in Church Street, Chelsea. The room was practically innocent of furniture. There was no carpet on the oaken floor. No pictures on the walls. A table without a table cloth stood in the middle of the room. There were one or two chairs distributed round the room but the women sat on cushions or mats. There were about twenty women present, of all ages, and degrees of beauty or rather plainness. D’Estesse is a funny little woman, whose costume is conspicuous by reason of its studied unconventionality. It consisted as far as I remember, of a sort of blue overall. Her hair is cut short, like a man’s. She both reads, and writes, beautifully. She can also evolve a logical chain of argument, which was a comparatively rare gift among women until quite recently.

The subject was ‘Are we all Greeks?’ Madame D’Estesse maintaining with considerable ability that we are not. Then Madame Cavalho made a very able speech in favour of the thesis. As they had omitted to define what was meant by the term Greek, both were able to conclusively prove their contention.

I went down to Walworth to lunch with Strong, who is the curate of the parish. The streets are broad and well paved and the houses new and well built, but they produce an indescribable impression of dreariness. The people, men and women, who one sees in the street, look oppressed and apathetic. As though work, and the incessant struggle with penury had stamped all feeling save a sort of dull aching pain, out of them. Still I suppose they have their moments of glorious life. I suppose that love, at some time or other, lightens up their homes, and makes the dreary asphalt streets seem like golden roadways, and the world a fairy land of brilliant possibilities. Those thin, worn looking women, in ragged black dresses with aprons of sackcloth, who are scrubbing the steps of their humble homes, while ragged children play about in the roadway, has love ever kissed them and have they woken from their delusive dream, to a life of toil and misery?

Strong lives in a workman’s cottage, in a dreary street of workmen’s cottages. He must live a terribly lonely and depressing life. He has not even got the satisfaction of knowing that the poor of Walworth are grateful to him for what he does. I asked him if they ever showed any gratitude and he answered:“No. They seem to regard it as a supreme favour on their part, allowing me to interest myself in them at all. They treat me as if it was an amusement to me, and that it would be a shame to spoil my fun.”

In short, they patronise him. It is rather amusing to think that the poor consider they are patronising the rich who set out to patronise them. For if they take up this attitude with Strong, whose whole life is lived for and with them, they probably do so in a far higher degree with the mere charity monger.

We were afterwards shown over the workhouse. This really is an infirmary with 1400 inmates. There are no able-bodied men, only a few able-bodied women. The majority of the inmates are old people of both sexes who have come in to rest from life’s battle, before they enter on the final sleep. Some are able to carry on the light work of cooking, and washing and cleaning out the workhouse. Others can only sit all day and sew, while some are completely bedridden. This is a very sad sight to see all these poor old people, most of whom have said good bye to the outside world for ever. Many of whom suffer continually, all of whom have nothing but the grave to look forward to. Yet probably the calm of the workhouse seems sweet to them, after the long struggle which their life must have been.

We went through all the wards. Old people were sitting with their faces buried in their hands or lying with closed eyes in their beds. In one ward, an old woman came forward and recited Shakespeare’s Seven Ages of Man to us without a single mistake, or any hesitation. She was evidently a woman of education and refinement who had come down in the world. The workhouse master told me that it is by no means uncommon to get educated people in. They had quite recently had a clergyman, who spoke five modern languages, besides being a brilliant Latin and Greek scholar. Drink had been his ruin. The old ladies in the sewing room looked like a lot of old chickens; they sit all day and gossip and sew.

At least the old people are well treated, well cared for and well fed. The workhouse seemed a model of discipline and order, and is entirely self-contained. It has its own steam laundry and bakery, and water supply etc. Practically all the household work is done by the more able-bodied inmates. The Master is a naval warrant officer, and although a rigid disciplinarian seemed a kind hearted man.

We afterwards went to the Pound School and saw the infant classes. One class came out and danced in the hall while we were there. They have substituted dancing for the more rigid system of drills and military exercises. The children danced a Sir Roger de Coverley, remarkably well, and then danced and sang to the tune of “London Bridge Has Tumbled Down” etc. Each little girl had her little boy partner, who treated her most gallantly. The children were as graceful and happy as fairies. I think little girls are born with the knowledge of their powers of seduction, certainly they all smiled at us as they went past in such a confidant, bewitching manner, that we were all quite fascinated. These happy little creatures, whose average age must have been ten, and who were dancing their way into a world which seemed all sunshine and smiles, made a striking contrast to the worn out old in the workhouse. Will the world fulfil its promise of happiness to these little ones? To a few perhaps.

I afterwards had to go to the “Daily Mail” office and interview the Editor, Marlowe, with a view to being taken on their staff. I regard Carmelite House as the outward and visible sign of the most hateful development of modern times, to whit – the Press. Marlowe was very friendly, and seemed quite a respectable person, despite the peculiarly revolting function which he performs. He turned me over to an individual called Fish, who is news editor. He directs that horde of hungry vultures, the reporters, who are always pecking about in the refuse heaps of a great city in search of ridiculous little pieces of news. The halfpenny newspapers have proved conclusively that the majority of men are fools, who worship the banal.

Monday 5th March 1912

A day of portent. The coal strike was declared last Friday, and every day reports from all over the British isles, show that the volume of unemployment grows apace. The pinch of hunger is already being felt by many workers in the less well paid industries of the country, who have been cast on the streets by reason of the miners’ activities.

All day long, in London, the streets of the West End have resounded with the crash and clatter of plate glass windows, falling before the hammers of the suffragettes. March has set in with storms and the day has been wet and gusty. Here and there animated groups were to be seen, gathered around some screaming woman, who was being led struggling to the nearest police station.

In view of the intended suffragette demonstration, all the approaches to Trafalgar, Parliament Squares, are filled with dark companies of policemen and from time to time mounted police come clattering down the street in parties of two and threes.

At about five o’clock the sun came out, tingeing the driving storm clouds with a crimson glow, and casting a roseate reflection on the glistening street. Animated crowds were hurrying down the Strand, and all the other approaches to Trafalgar Square, anxiously expectant of some incident to break the monotony of their existence.

I came out of Carmelite House and wandered home along the Embankment. The night was fine, but the wind howled among the chimney stacks, and came tearing down the streets. The sky was not black but rather the colour of a clouded amethyst, and studded here and there with stars. A barge drifted moodily down the Thames, the tide rippling in silver eddies round its sides. The river runs with the glimmering reflections of many lights, while from time to time the wind passed like the shadow of death across its surface.

The spirit of unrest was abroad in the night. Even the shivering loafers had left their accustomed benches, to wander restlessly up and down the embankment. The distant thunder of social revolution could be heard in the elements. The death throes of an epoch could be heard in the storm.

Saturday 25th August

I feel about at the end of my strength. The 8 months of night work and constant nervous strain over the Daily Mail have exhausted me. The sordid futility of the whole thing has thrown me into a constant state of revolt. I have lost my self-respect through consenting to be stupid and to produce stupidity for the wretched salary of £4 a week.

Miss Fairfax has gone away to Yorkshire. She was a great comfort to me and I miss her. She is hopelessly unpractical, but an artist by nature and she understands. She knows what a misery the Daily Mail has been to me and she knows how ill I am. I am staying with the Cooks at Argyll Lodge. They are kind to me, and make excellent hosts. Mrs Cook is always thinking of her guests’ comfort, and is kind with that unostentatious simplicity which is the chief characteristic of the ‘gentleman’. Mr. Cook is also kind, and a charming host, but is incorrigibly fussy. It is a form of nervous irritation I think, produced by pain. He finds fault with everything, like a spoilt child, and makes life a constant worry.

Mignon, my “dear little comrade,” completes the trio. “Dear little comrade” describes her better than anything else. She at once recalls and realizes the lines of Baudelaire.‘Que m’importe que to sois sage‘Sois triste et soit belle.’She is certainly not clever, but has sufficient intelligence, and is fond of poetry and beauty, and is saddened by the fever of eternal discontent. She is a bohemian at heart, and consequently a good comrade. She has rich sensual lips and dreamy eyes with long eyelashes, a slim, alluring figure with finely modeled, delicate limbs. She is incapable of fidelity being a child of nature, yet she is affectionate and charming. She has a restless almost feverish longing for change and excitement which so often heralds incipient consumption.

In the evening Mignon and I went to the Hippodrome. I did not enjoy the performance as I was too ill and tired. Seymour Hicks and Ellalaine Terris gave a sentimental play of the most revolting variety and some Russian dancers did Sheherazade. I am tired of the Russian dancers and the barbaric splendor of their costumes and scenery. Their art is so erotic and has no part in our life. It awakens no sympathy, and like modern woman’s dress its aim is purely erotic. One longs to see some trace of nationality in our art, it has become so cosmopolitan. It is designed to please the rich minority which is cosmopolitan and sensuous. The constant tendency of the English people to deprecate anything English, is fatal to an artistic development.

In the taxi-cab on the way home dear little Mignon fell back into my arms with charming grace and half opened her beautiful lips as if athirst for kisses. Her white breasts had escaped from the prison of her corsage as she lay there in my arms a picture of beautiful desire. Our brief spell of folly was interrupted by the arrival of our taxi at Argyll Lodge and our awakening was completed by the voice of Mignon’s mother, insistent for details of the Coliseum performance. When supper was over, and I had gone up to my bedroom a feeling of intense nausea and weariness came over me. I felt how little were kisses without love: how sterile desire. I do not love Mignon at all, in the spiritual meaning of the word. She was merely the realisation of some of my material desires.

I could not sleep; I have been unable to do so for some time past. At 3am I could endure the solitude of my bedroom no longer, so getting out of bed I put on coat and trousers over my pyjamas and slipping my feet into my bedroom slippers I crept downstairs and out of the front door. The stairs seemed to creak inordinately, but still I awoke no-one. I shuffled up Gloucester Road, to No 2 Queens Gate Terrace. The door was locked and bolted but after some time I succeeded in attracting the attention of the caretaker. I found George in bed (probably his brother George). He was asleep but the sound of his door opening awakened him and he sprang out of bed with a bellow, as if he imagined I was a burglar. He had been to a dinner given by some man who was about to be married and had only just got to bed. I think that he was a little drunk. Anyhow he insisted on getting up and coming out with me into the streets.

It was dawning. A horrible cold and yellow dawn. We passed one or two shivering half-starved wastrels shuffling along with their hands in their pockets. We went up the Brompton Road and along Knightsbridge and Piccadilly to the Turf Club cab shelter. There we stopped for some bacon eggs and coffee which George recommended. There were five men in the shelter. Two of them, taxi cab drivers, were playing dominoes with an old matchseller. The matchseller was a man of enigmatic age. He was fat and his cheeks flabby and apparently bloodless. We learned afterwards that he practically never slept. After stamping the streets all day with his merchandise he entered the cab shelter to play dominoes until the dawn.

The taxi cab driver who sat next to him was a man of sallow coarse complexion, with a sinister cast of countenance. His face was expressionless save for a vague air of weariness and indifference. He played in silence, not speaking once during the hour and a half that we remained in the shelter. The third player, also a taxi-cab driver, was more communicative. He had a pleasant rather stupid face. He preferred night work, it was quieter. When I asked him if he did not miss seeing his pals in daytime he remarked, ‘It aint much good seeing your pals when you aint got no money to spend.’ I gathered from his subsequent remarks that the motor cab trade like every other was overdone and that it was hard to get a living.

I feel much worse today and in the evening George went to the Daily Mail office to say that I could no longer continue work. I spent most of the day with Mignon and in the evening after dinner we set off for a wander through the streets. The park was crowded with loving couples who swarmed everywhere like bees. There was breathing space round the lamps, however, for the lovers shunned the indiscreet light. We wandered arm in arm across the row to where the band was playing some futile waltz but there the crowd was so thick that we crept over to more secluded regions.

Then as a damp crawling mist crept up from the roots of the trees stifling like a shroud the laughter and happiness all round, we left the park. At Hyde Park corner we struggled in a surge of eager persons in their Sunday best for a seat on top of a great panting motor omnibus. And being successful were whirled off with a clatter and a roar through a seething artery of traffic towards Victoria. Crowds of uncomfortably smart looking holiday makers were converging from all direction on the station to catch the homeward train to some suburb after a glorious day in the city. We went on down Victoria Street to the Houses of Parliament. Mignon was leaning on my arm, her breast just pressing my shoulder with a caressing confiding abandon. In Parliament Square, opposite Big Ben we stopped and instinctively faced each other then regardless of the passers-by I kissed her on the lips and we went on to Westminster Bridge where leaning on the parapet we looked out onto the river. It was a patchwork of scintillating, distorted reflections. The river was very hushed and quiet and the shadows on the water very deep, while behind us rushed around the traffic, the motor omnibuses shaking the bridge like angry Titans.

We were impressed with the quiet beauty of the scene and stood so long gazing out into the shadows that the intensity of our concentration attracted the fleeting attention of a bored policeman, who took up his stand close beside us. I think he imagined that we contemplated suicide.Thereafter a long long wander down the Embankment, through the broad, prosperous deserted streets which skirt those great houses of rest, the government offices and past the quaint old – so essentially nautical - admiralty and the gilded idiots on chargers outside the horseguards, we finally gave out at the Carlton Hotel,. Hailing a taxi we drove home, Mignon resting her little head on my shoulder. I kissed her closed eyelids which were weary with much longing and then the taxi stopped, the metre bell rang, and once more we had to face Mrs. Cook’s trail of lifeless futile questions, and Mr. Cook’s reflections. Then bed, and after a heavy dose of morphia, thank god, sleep. Long refreshing sleep.

Monday 27th August – going to stay with Capel Cures

After a busy morning I left Paddington at 1.20 for Salcombe to stay with the Capel Cures. Mignon came to the station to see me off. The platforms were crowded with holiday makers and everyone thought it necessary to hurry although most of them had probably time and to spare. Mignon and I walked up and down the platform arm in arm until the last minute. Then I kissed her on the lips and we parted.

I sank back in my carriage seat with feelings of great relief at escaping for a time from the restlessness of London life and from the feverish activity of the Daily Mail office. For weeks my brain had been in a confused whirl. I had had no proper sleep, and had lost the power of forming a rational judgement on life, or indeed on anything. My mental perspective was completely deranged, and the smallest worries assumed in my distorted mind the importance of great troubles.

Esther Capel Cure (she will be his wife) and her father met me at the Kingsbridge Station and we motored to Salcombe in their new 16.20 hp Sunbeam car. The welcome that this charming family gave me dispelled for a while all the gloomy clouds of foreboding and depression which oppressed my brain, by reason of its simplicity and its sincerity. As a family they are delightful because they wear no masks.  They have none of the artificiality and affectation which people seem to develop as soon as they mix in “society”. They have the candour and simplicity of great works of art. They are intelligent and talented. The mother plays the piano with unusual grace, Sylvia is almost a first class pianist, and Esther is a good violinist, sings well and has a genius for teaching others to sing.* The father is a quiet, strong, cultivated English gentleman and a man of business. He has had to fight with great difficulties, for soon after his start in life, he suffered a succession of serious illnesses. He was faced with apparent ruin and an early death, but he and his young wife struggled on with undiminished courage, and now they have conquered all difficulties and have their reward.

They have none of the artificiality and affectation which people seem to develop as soon as they mix in “society”. They have the candour and simplicity of great works of art. They are intelligent and talented. The mother plays the piano with unusual grace, Sylvia is almost a first class pianist, and Esther is a good violinist, sings well and has a genius for teaching others to sing.* The father is a quiet, strong, cultivated English gentleman and a man of business. He has had to fight with great difficulties, for soon after his start in life, he suffered a succession of serious illnesses. He was faced with apparent ruin and an early death, but he and his young wife struggled on with undiminished courage, and now they have conquered all difficulties and have their reward.

I suppose if they had not struggled and suffered, they would not have the broad sympathetic outlook on life which is their greatest charm. That they would not have a noble scorn for those glittering superficialities and conceits which so many people regard as life. They are a family of Christians, Christians in their life and actions. This is what makes them so happy, and what makes happy those who come in contact with them. It is only since meeting them that I have begun to grasp the meaning of Christianity. The Christianity they teach in their lives is quite free from cant and humbug, and hymnsing and ritual. The hypocrisy of infallibility has no place in it. It is a Christianity which does not condemn, but which is beautiful by reason of its sympathy with human failings.

Esther Flower, the elder daughter, is about 25. She has great strength of mind and determination. For the past three or four months she has been teaching me to sing. I have been a trying pupil for my nerves have been in a shocking state. Yet never for one moment has she lost heart or failed to encourage and cheer me. She in engaged to a young man called Bradshaw, who was educated as a pianist and who, finding it impossible to earn a living by his art, has taken up massage as a profession. His people have a little house on the opposite side of the creek to the Capel Cures.  He used to sit in his studio and play the piano, and on the opposite side of the creek Esther would lay down her violin and listen to him, wondering who was playing so beautifully. At times he would listen to her singing and so a subtle sympathy sprang up between them. Then one day they met, and soon became engaged. Her father had never met the young man and when he heard of the engagement was furious. He refused to meet the young man or to allow his daughter any money to marry on. They were quite undeterred and Esther has settled down with great determination to make a little money by giving violin and singing lessons, while her lover continues his massage and one day when they have enough they will marry and probably be quite happy.

He used to sit in his studio and play the piano, and on the opposite side of the creek Esther would lay down her violin and listen to him, wondering who was playing so beautifully. At times he would listen to her singing and so a subtle sympathy sprang up between them. Then one day they met, and soon became engaged. Her father had never met the young man and when he heard of the engagement was furious. He refused to meet the young man or to allow his daughter any money to marry on. They were quite undeterred and Esther has settled down with great determination to make a little money by giving violin and singing lessons, while her lover continues his massage and one day when they have enough they will marry and probably be quite happy.

Midget (Sylvia) is of a more timid and less independent nature. I think she would let her heart break sooner than disobey her parents.

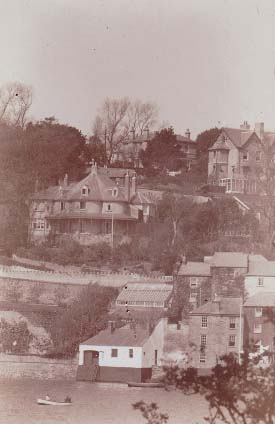

The Grange stands on the hill overlooking the village on the south side of the creek. It is built on the steep slope of the hill and the one acre of garden is a succession of terraces and of precipitous gravel paths. A veranda runs along the length of the front of the house and some ten foot below the level of this verandah which is on the ground floor is a grass terrace. From the house one looks out onto the creek, bordered on both sides by steep and high hills and out beyond to the harbour mouth. The entrance is guarded by two rocky and rugged headlands, which stand guard like sentinels. Further in is a sand bar, which in rough weather can only be crossed at one place. When the sea is rough one can hear a monotonous moaning sound coming from the white tormented breakers which foam over the sand. It was here that Tennyson wrote ‘Crossing the bar.’ The creek runs inland some eight miles to the town of Kingsbridge, where the railway ends. I had to spend Monday night among the servants in a narrow little attic, which resembled nothing so much as a dog kennel, because the only two spare bedrooms were occupied by Mr. Murray Davy and his wife.

*When I cleared Whimbrel’s (his eldest daughter) house, there were few papers left but among them was thisreport from The Royal College of Music:‘I have the honour to state that Miss Esther Capel Cure was a pupil of the Royal College of Music for twenty-seven terms between May 1898 and July 1908, taking Violin, Singing, Pianoforte, Harmony and Counterpoint as her studies. She attained to a very distinguished position in the grade list for her principal study, the Violin, and was one of the most brilliant, efficient, and dependable Violinists in the College, taking part frequently in Concerts, always with eminent success; and she even for a time led the Orchestra, which is a position of responsibility which can rarely be entrusted to a lady violinist.She also did very well in her other studies, and thus proved the scope of her musicianship. She won an exhibition for Violin playing in 1906, and passed the examination for the Associateship of the College in the same branch in 1908. Her career at the College was thus in every way eminent and honourable, and her musical gifts were happily seconded by a most estimable disposition.C.HUBERT H. PARRY Director, R.C.M. And then:‘Miss Capel Cure has been my Pupil for several years at the Royal College. She is an excellent Soloist as well as a Quartet player. I am pleased to recommend her as a proficient teacher as she possesses all the necessary qualities to be most successful with her pupils.ACHILLE RIVARDE

And then:‘Miss Capel Cure has been my Pupil for several years at the Royal College. She is an excellent Soloist as well as a Quartet player. I am pleased to recommend her as a proficient teacher as she possesses all the necessary qualities to be most successful with her pupils.ACHILLE RIVARDE

When I read this passage to Avocet, she opened her mouth and out came:

Sunset and evening star,

And one clear call for me!

And may there be no moaning of the bar,

When I put out to sea.But such a tide as moving seems asleep,

Too full for sound and foam,

When that which drew from out the boundless deep

Turns again home!Twilight and evening bell,

And after that the dark!

And may there be no sadness of farewell,

When I embark;For though from out our bourne of Time and Place

The flood may bear me far,

I hope to see my Pilot face to face

When I have crost the bar. (Crossing the Bar by Alfred, Lord Tennyson)

Friday 13th September 1912 Shooting up the creek

It was nearly two oclock when we crawled down the sandstone cliff to the cover where the dingy was waiting to take us off to the punt. Jarvis, the fisherman was waiting for us and as we arrived he touched his cap in his slow, meditative manner.

“Well Jarvis, is there going to be enough wind to sail?” Jarvis looked out seaward over the bar, sniffed, took off his cap by lowering his head toward his hand and letting it drop off – a way sailors have, scratched his head, put his cap on again, sniffed and then replied

“Yes Miss. I think we shall get a nice little bit of breeze up the creek.”

“Never mind the breeze Jarvis” C (Mr. Capel Cure) joined in, “Do you think we shall get any curlew?”

Jarvis repeated the process, save that he omitted to take off his cap, and gazed long and earnestly up the creek as if seeing mysteries of nature which were hidden to our lay eyes. This was pure affectation on Jarvis’ part, as we afterwards discovered that he was almost as blind as a bat and never sighted any birds until C had attracted his attention by shooting at them. We were all three wearing long rubber sea boots so we splashed through the water with the dingy while Jarvis rowed us out to the larger boat. There was not a breath of wind. Jarvis took one oar and I took the other. Esther, who made a quaint figure in her long sea boots, and wide straw hat such as is worn by the peasants in the Canary islands – curled up in the stern sheets, while C with his gun held carefully in one hand took the tiller.

The water looked like molten lead. Out at the mouth of the harbour, we could hear the swirl of water over the sand bar which lies between the two black headlands but here there was no motion on the water. We found a number of yachts lying lazily at anchor. One, a great white steam yacht of about 300 tons, had only just come in. A group of well dressed people were sitting on deck under an awning. Two of them walked to the ship’s side and leaning over watched us as we rowed by. They seemed astonished that any human beings could voluntarily exert themselves in such weather. Just then a servant brought out a card table and we saw them start a rubber of bridge.

Jarvis and I rowed on with short monotonous strokes. The roll of our oars in the rollocks and the gentle swish of the water under our bow, had an intensely soporific effect. Esther had closed her eyes and was sleeping peacefully. I had almost dropped asleep as I rowed. We passed a beautiful little white sailing yacht, with a slender hull lithe as a hound. She was standing out towards the harbor mouth, her long thin hull gliding like a shark through the water, and her sails were filled although we felt no touch of wind. Then as she passed us we felt a gentle puff and a sylph passed over the waters. The yacht heeled over at an absurdly acute angle, then we knew she was bringing the breeze down the creek with her. Jarvis lay on his oar with a sigh and I followed his example. Then after a pause he said to C:

“What about shipping a mast and sailing up the creek sir?”

“Do you think there’s enough wind?”

“Yes, sir. There’s plenty of wind round the point.”

“Well if you think so Jarvis,” C replied.

“I do, sir. She is a wonderful sailor in a light breeze.”

This was a manifest untruth for we all knew her to be heavy, sluggish in stays, with an infinite capacity for making leeway, but experience had taught us never to enter an argument with Jarvis.Jarvis was in the act of getting up the mast, setting the brown leg of mutton sail, when he suddenly stood stock still in the boat with his back turned to us, took off his cap, scratched his head and ejaculated,

“Well I do be blest.”At the same moment we became conscious of a swirl and a swish on the water which was churned up a short distance astern of us in a silvery foaming torment. Then we saw a shoal of silver mackerel not twenty yards astern. The next instant they were all around us, jumping and glistening like a shower of silver in the sunlight.

“Well I do be blest. Mackerell!”And he turned regretfully to finish setting the mast. The mast was set and the mainsail hoisted. I took the tiller, C sat with his gun at the slope. Rose Esther remained curled up in the stern and took charge of the main sheet.

“What an extraordinary thing,”echoed Rose Esther.

“Well it be the first time I seed them beggars come right up creek like that. Why, if we had a net we could catch a pretty lot of them.”

A puff of wind came tearing in a thousand ripples towards us across the water. The brown sail filled, the halyards strained and creaked, Rose Esther clung on for dear life to the sheet, and the boat staggered and heeled for a moment, then righted herself and glided forward, the water lapping in laughing playful spat against her bow. As we rounded the point, a gust of wind caught us and she heeled over till her gunwale was almost awash. Rose Esther eased off the sheet and I luffed her up into the wind, where she hovered with fluttering sails for an instant like a sea bird hovering over its prey. Then as the wind died I eased off again, and we reached up the creek.

The tide was at full ebb, already round the sand banks we could see the swirl of the flood tide. For about three miles either side stretched grey, slimy, shimmering mud flats, intersected here and there with winding canals. On the outer fringe of the mud, stood an army of solemn looking sea birds, crying all and at the same time but each with a different note, so that the air was full of their weird, discordant plaintive chorus. The breeze had freshened and we were tearing along, the water foaming under our lee gunwale. The wind against the flood tide, which was by now sweeping up the creek – had churned the water into short nervous waves. Every now and then a whiff of spray came over her bow, wetting C and his gun:“Luff her, luff her, man. I don’t want to get my gun wet,” he cried, but all the luffing in the world would not have kept her dry in that chaos of angry waves.We were now quite near the mud, as we approached a number of curlew rose and flew off with lumbering haste inland. The gulls seemed to know instinctively that they were not quarry for C’s gun, and regarded our arrival with indifference. We put about and tacked across toward the bank. A wild duck with long outstretched neck came tearing down the creek in superlative haste. C took a shot at him, but he was out of range and turning in a wide circle made off inland.

“I expect ee come from over Babbicane way,” Jarvis remarked.

“Just came over to see whether Salcombe was a nice place to bring his wife and children for a holiday I suppose,” said Rose Esther with a laugh.

“Yes, Miss,” answered Jarvis. “I don’t suppose they will be coming Salcombe way this summer now Miss.”

The breeze had increased to such an extent that it was impossible to keep the boat dry when sailing, so we lowered the sail and Jarvis started to pull her up the creek. We crept up a narrow creek between two banks of slimy mud and waited there for unsuspecting birds. We had not long to wait before Rose Esther cried "Coming over." A flock of the graceful grey birds was flying towards us at a great rate down the wind, C fired right and left.

The whole flock swerved off almost at a right angle, then righted itself and made off across the stream, all save two which came fluttering down in the mud 20 yards away and lay quite still. Jarvis was over the side in an instant, and climbing up the mud bank. He had not gone ten yards, however, before he sank up to his knees in the black oozing mud. I jumped out to go to his rescue, forgetting that I was wearing C’s sea boots and that they were 2 sizes too big for me. I sank of course in the mud and in my struggles to be free left the boots behind.

Then Rose Esther lit on the bright idea of throwing me a bottom board, upon which I stood. Then she threw a second and by means of picking each up in turn and placing it before me I was able to walk on the mud and retrieve the birds. We waited a long time between those mud banks but no more birds came. We did not mind because of the physical enjoyment we experienced in our surroundings. We were sheltered from the wind and a glorious sun beat down on us, gilding the shiny mud flats with a thousand brilliant colours till they looked like glistening porcelain mosaics. The tide swept by the boat in musical lazy ripples lulling our senses almost to sleep while overhead seagulls hovered. The air was filled with a delicious scent of seaweed and ozone, with which mingled the perfume of wild flowers and hay.

Far above us a heron came sailing majestically down the wind. The harmony of our surroundings was interrupted by the report of C’s gun. This time he had brought down a beautiful little ringed plover, which was digging harmlessly about in the mud in search of a meal. Both Rose Esther and I inwardly cursed C and wondered why he always thought it necessary to kill something whenever the weather happened to be fine.

A cold breath from seaward warned us that evening was falling. We rowed out backwards into the main creek. The wind had dropped, and the waters were still save for the gentle lapping of the tide around the mud flats. Most of the mud was covered now, and all along the edge of the water stood a line of sea birds, searching for the jetsam of the flood tide, for the small sand eels that the sea drives landward. Further down two men were drawing in a reining net and we could see the glint of the sun over silvery struggling fish. The hush of the evening had descended on the creek; we were all silent, lulled by the roll of the oars in their rollocks. We rounded the point and opened out the harbour. The sun was just disappearing behind the hills, and a golden bar lay across the black headland. The glow of the evening was on our faces, and we seemed to be rowing towards a sea of rose and gold.

23rd December 1912 Salcombe. Christmas

On Monday we went up the creek with the draw net. Jarvis, Mr. Capel Cure, myself and Hobbs formed the crew of the Shag, while Crofton the chauffeur sat upon the net which was piled up in the stern. Ester, Midget (Sylvia?) and Mrs. Capel Cure we towed behind us in the Tildew. It was a grey winters day but mild as in summer. Outside a southerly gale was blowing up the channel, but here in the creek we were sheltered from the wind. A long uneasy swell was rolling into the harbour mouth, breaking in a line of foam across the bar and dashing in frothy cataracts over the many isolated black rocks which dotted the harbour. The tide and wind were behind us, and four of us were pulling, so we made up creek at a good pace, slewing along on the tops of the waves and then sagging back into the hollows.

Hobbs displayed much energy and enthusiasm. He was gardener by profession but would have preferred being a fisherman. Jarvis, the boatman, on the other hand had never felt the call of the sea, but had a passionate fondness for flowers and farming, neither of which he knew anything about.Crofton, who is chauffeur in his leisure moments, regarded the whole proceeding with an air of lofty indifference born of an intimate acquaintance with carburetors, magnetos, and other technical miracles, which made our fishing expedition appear primitive and unworthy in his eyes.

Jarvis was the great weather expert, and it was always a point of honour that he should be consulted on all occasions, so Esther, who always remembered everybody’s due, hailed him from the Tildew asking with a feigned Devonshire accent:

“Well Jarvis, and what be the weather going to due.”

Jarvis interrupted his rowing, to slowly take off his cap, scratch his head, and survey the heavens. After a few minutes he replied:

“It due look as if we should have a bit more wind, Miss Esther. I don’t like the look of they great big fellers with their dogs out behind they. The wind don’t seem to be able to get by Miss.”

Jarvis returned to his rowing. I wondered what he had meant by “they great big fellers with their dogs out behind them,” and where the wind was to get back to, and why, and what would happen if it did ultimately succeed in accomplishing this apparently difficult task, so I whispered to C, asking him what Jarvis meant and he explained as follows, “He doesn’t like the look of those great big clouds, with little clouds blowing by beside them, and he thinks the wind would calm down if it could get from south west back toward the north again.”

The sea gulls were flying restless in circles above our heads, and as we approached the mud flats some frightened curlew made off down wind, while not far off black headed shags were floating on the grey water every now and then disappearing beneath its surface in search of fish. Jarvis explained to me how these birds eat seven pounds of fish daily which cannot be much less than their own weight. On the slope of the hills beyond the mud flats two great horses were pulling a plough across the field of rich red earth, while a flock of noisy seagulls followed in its wake, searching in the steaming earth for the worms which were turned up by the plough share.

At ? point we landed, splashing through the water in our sea boots which sank well above the ankle in the shiny black mud. Then while C and I held the end of the grass hawser Hobbs and Jarvis rowed out to sea in a circle dropping the net overboard as they went, returning to the shore almost one hundred yards higher up the creek with the grass hawser attached to the other end of the net.

Then we all manned the ropes, marching towards each other as we hauled, until just as the line of corks reached the shore we met then hauled in on the leads until the whole net was high and dry on the beach. But instead of a teeming catch of silver breasted fish, we had caught nothing but a dozen or so bottles, a hermit crab, who succeeded in cramming an immense quantity of legs and claws into a tiny shell, a scallop, some dozen common or garden crab, all too small for practical purposes.

Jarvis took it very philosophically, remarking “You see it due be getting very late in the year sir.” He had memories of many similar expeditions, all of which had proved greatly fruitless. Hobbs was less philosophic, and behaved as Jarvis would have in his garden at home, had the roses failed to bloom. Crofton became more supercilious and superior, being now fully convinced that fishing was the sport of fools. Esther and Midget were busy poking about the rocks in search of oysters. As for C and myself, being simple people, we were quite satisfied with the aesthetic enjoyment of this morning on the mud flats, with the water lapping at our feet, the seabirds wailing in the gale above our beach, while a little boat sailed up creek, against the wind, foam at her bow and a line of foam along her lee side where the gunwale lay low on the water.

We repeated the process several times further up the creek but each haul was barren of fish, resulting only in the reaping of a rich harvest of broken bottles, of which the bottom of the creek appeared to be chiefly composed.

15 January 1913

Today I went up to Harrogate to give a lecture on the war as I saw it, before the Harrogate Literary Society. I expected that the literary society would be a select gathering assembled in a small hall or drawing room for the purpose of hearing an intimate talk on the war. To my surprise I found an audience of some fifteen hundred persons assembled in a hall about the size of the Palace Music Hall.

This was my first appearance on any public platform, and indeed the first speech that I had ever made. I was in every sense obsessed with nervousness and longed for the stage to open and swallow me up. The lecture, however, went off pretty well, only I failed to apportion my time correctly and had to cut short my description of the latter phases of the war.

The audience seemed fairly intelligent and quick in grasping a good point, but were stolid and undemonstrative. Mr. and Mrs. Douglas Grey, the rector of St. Stevens High Harrogate, had kindly invited me to stop with them on the night of my lecture. I arrived there at about 5 o’clock, and was received at the door by a sad looking man who I think in his lighter moments must be accustomed to fulfill the duties of grave digger and bell toller. He showed me into the drawing room where I was soon afterwards joined by Mr. Grey, who bid me welcome to Harrogate. A dried up rather pedantic but withal kindly man of about fifty, he seemed to have become petrified by the routine of church life. The constant struggle entailed with a diminishing income and an increasing family had saddened his outlook on life. I think he was sick to death of his life in the rectory, and talked with enthusiasm of winter months spent in skiing on the pure white snows of Switzerland and Germany. Mrs. Gray joined us at tea time. A kindly, red faced, happy, healthy old lady, she seemed absorbed in the interests of her family, and exuded a certain warm and generous glow of benevolence toward mankind in general. I felt sure she must have been the mainstay of the parson’s rather drooping spirit. The whole family talked of emigrating to British Columbia, whither one son and daughter had already gone in search of a healthier, happier, life.

8 January 1913

Today I went down to Bognor in Sussex to deliver Ellis’ (his brother, who will become a famous war correspondent) lecture on the war for him at the local Kursall. Bognor is a melancholy, deserted seaside place whose inhabitants seem sunk in a profound and impenetrable miasma of depression and inertia. I stayed at The Royal Norfolk Hotel. During dinner I was accosted across the room by a red faced, heavy, rather bestial individual who said: “I expect you know my father Sir Henry Moler.” The heavy-jowled individual proved to be the present Lord Wolverhampton. He went on to talk of the various political leaders in both houses with an air of affected intimacy. He was very slow of perception, it taking some minutes for a remark to penetrate into his stagnant brain. He told me that he had been at Bognor for three months, a lamentable fate, because he was “doggy”. I was at a loss to understand what he meant by doggy until he went on to describe how he was interested in coursing and kept greyhounds. I suggested that he must have found Bognor dull, to which he answered that there was always something to do when “one was messing around with dogs.”

I went on to the Kursall having some difficulty in getting the cabman to understand my exotic pronunciation of the word, until the porter came to my aid explaining to him that I meant the “Curse-all”.At the Kursall I explained to Chamber, the agent of Baring Brothers, that I had come instead of my brother who was ill, and asked with some apprehension if he thought that it mattered. He was a lugubrious, miserable but withal shrewd looking individual, with a red nose.

“I don’t think so, there ain’t no-one in the all.”From over the way came the grinding of many skates on a wooden floor, and the strains of an orchestra in confirmation of his gloomy prognostication.

“What?” I exclaimed, “No-one in the hall?”

“Naow,” he replied, “only two pounds advance booking, still there is plenty of theatrical companies what don’t do as well as that.”

“But what is the meaning of it.” I answered. “Will some come later on?”

“Don’t suppose so,” he replied, “What can you expect at a place like Bognor, why the very name makes you feel sick. Besides all the people is too depressed by the weather to come out of an evening, and what there is is at the skating rink.”

“Well,” I said, “Don’t you think that you had better go on the stage to say that as my brother is ill, I have come to give the lecture in his place?”He was getting sadder and sadder, as if crushed by years of opposition to immoveable fate. When I finally faced the scanty house as my brother, I was greeted with a loud cry from a man in the gallery of

“Daren’t do it guvnor. They would all ask for their money back. You as to treat them kindly where they sits lonely.”

“Ere what about that smug looking fellow what’s on the programme?”Then I remembered that every programme had my brother’s portrait.

The clerk with superb presence of mind switched out the lights, and I heard the sounds as of a man being stifled in the gallery but apparently he escaped his oppressors for a moment afterwards came a stifled cry of

“Ere, what I wants to know..”and then sounds of a man being choked while from the other side of the gallery came an answering shout of

“Yer wants too much. This aint a blooming beauty show.”

12 January 1913. Being Ellis in Folkestone. Lecture in Paisley

At the last moment Ellis decided that he must go to the fancy dress ball of the Three Arts Club at the Queens Hall with Mlle Gina Paloma, and consequently asked me to give his lecture at Folkestone for a fee of £10.10.0. This I accepted to do and accordingly took the afternoon train down to that place. When I arrived at the Town Hall about a quarter of an hour before the time for the lecture to start, I was met by Candler, the managing agent, who was surprised to see me instead of Ellis.

“O lor,” he exclaimed “You don’t mean to say that he ain’t come up to the post again?”

“Yes,” I replied, “he has a bad cold and has completely lost his voice.”

Then Candler introduced me to a lady whose name I forget, but who was very charming, and who was in charge of all the arrangements. She seemed disappointed at not seeing my brother, and skeptical as to whether I could give the lecture in his place. Candler and I reassured her, however, and managed to inspire a certain amount of confidence.I insisted that Candler should announce my substitution for Ellis, not daring to repeat the imposture of Bognor, for fear that there might be people in the audience who would recognize me. At Bognor I had willingly taken the risk because I was unlikely to meet my personal friends in such a remote spot.

Candler was very nervous, but finally with the aid of a cherry brandy we got him onto the stage, and he made the following cryptic utterance.

“Lidies hand gentlemen. Mr. Hellis Bartlett has hunfortunately been hunable to come ere tonight because e as a bad cold. This ain’t altogether surprising lidies hand gintlemen, his it? Seeing as how what bad weather we as been aving.”There was a pause during which he fumbled nervously with his hat. Then pulling himself together he went on:

“But is brother, what saved is loif on the battlefield” (this was the first that I had heard of it, but the audience greeted it with loud applause)The Ebenger twins were two disreputable poachers who were figuring largely in the Daily Mail and Mirror as having become mixed up by the police and been sent to prison for each other’s sins.

“Is brother,” Candler went on with renewed confidence “ – as come ere in is stead. E went through the ole war and I don’t think that you will notice the difference has they his as much aloike has the Hebenger twins”. (more laughter)

The lecture was very well received by a fairly high class audience including a number of officers and their wives. The apotheosis of my career was reached when the charming secretary already alluded to produced an autograph book, and asked me to sign my name on the page on which figured those by Nansen, Shackleton and Amundsen.

I had to get up at six o’clock on the following morning in order to catch the seven o’clock train from Folkestone to Charing Cross, as I had to leave Euston at 10am for Paisley. I survived this terrible ordeal, and set out for my journey to the north, comfortably seated in a third class carriage with only one other occupant.

Our route lay through the great manufacturing towns of the midland and north such as Crewe and Sheffield. This great agglomeration of chimneys and vast furnaces belching forth a never-ceasing cloud of smoke and flames filled me with a vague terror. Men, who lived like ants compared with the size of the factories, were stoking the furnaces and minding the machinery. They live in grimy cottages all exactly alike, in grimy streets; they trudge through rain and shine to work in grimy, terrible, mighty factories, where the very grinding of the machinery seems to be tearing asunder the chains of their lives. Their towns are always covered with a pall of sordid smoke. They never see the sun, or the flowers of god’s earth; nor hear the song of birds in the fields, only the incessant roar of mighty machinery. How can such men care for Empire, or any of the dreams of statesmen. How can they evolve to understand national ideals, in their murky mist. What do they care for the intent of employers who have driven them to live and work in these uniforms of industry. I trembled to think that we in our blindness had confided the care of the Empire to men such as these, who in their squalor must clutch at any golden illusion held out to them by an ambitious demagogue

.Night had set in before we reached Glasgow, and for nearly two hours we seemed to steam through the succession of great flaming factories, which lighted up the clouds with a ghastly yellow glow and turned the heavens to one vast conflagration. From Glasgow I had to go to Paisley, a journey of about one quarter of an hour. I was rather depressed by the discovery that I had some difficulty in getting the porters to understand my southern accent, and wondered what would be the fate of my lecture if it fell on uncomprehending ears. A Paisley cabman informed that the two best hotels were the Temperance and the Globe,

“But you’ll no be able to get a wee drop to drink at the Temperance” he went on, “so I’m thinking you’ll feel more at home at the Globe.”As I agreed he soon transported me to that gloomy hospice, situated over some shops in the main street. On the first floor was a bar, from which an odour of beer and spirits spread out over the whole hotel. I cannot remember the exact colour and pattern of the wall paper and furniture but a sordid and yellowish brown hue seemed to predominate. My bedroom was undersized and the paper gangrened with damp and decay, while the bed was oversized and covered with a chilly and threadbare counterpane.

I asked for some dinner and I was led to the coffee room where a repast of chops and chipped potatoes, scones, butter, jam and tea was set before me. The coffee room was somewhat more cheerful having some tolerable pictures by local celebrities on the walls, and a roaring fire in the grate. After this high tea I made my way to the John Coats memorial Hall, where I was met by the Baptist Minister; a southerner by birth and with nothing in his clothes or manner to denote his calling. He seemed a very pleasant person, of more than average intelligence and with a keen sense of humour. He told me that a certain Mrs. Young wished to know if I would stay with her, an invitation which I as only too glad to accept, as I had no wish to return to the lonely parlours of the Globe after the excitement of the lecture.

The lecture was well received, the people of Paisley appearing to have both intelligence and a keen sense of humour. They were a trifle slow on the uptake, it took a few seconds for a joke to soak into their brains, but they then laughed heartily once it had done so. The lecture was a great success and I found the Paisley audience one of the most agreeable and sympathetic that I had addressed as yet. In this I was pleasantly surprised, for I had imagined the Scotch to be a dour and cold race whereas they appeared to me to be more humorous and warm hearted than the English, if such a term may be applied to the medley of utterly different races which inhabit the southern portions of our island.

After the lecture was over and the minister had said a few appropriate words, he introduced me to Mrs. Young, a nice looking fair haired, blue eyed woman of about 30 who greeted me in broad Scotch saying,

“You’ll be verra uncomfortable at the Globe Hotel, Mr. Bartlett, will ye no be coming to spend the night with us?”I replied that I was delighted, only that I should have to go to fetch my bag.Mrs. Scott and the minister drove down to the Globe with me, and waited while I packed my things. We then drove to her home, a decent suburban house, standing in its own scanty garden. At the house we found Mr. Young who added his welcome to that of his wife. Both were most hospitable, Mrs. Young entertaining me with a naïve hospitality which was quite charming. We had a good supper and then sat talking and smoking until late in the night.

Mrs. Young listened to my words with an excess of interest and deference which I found really embarrassing. I believe that she really thought that I was a personage of some importance. Both she and her husband were highly intelligent and well read. He had a very select library, and both could talk with knowledge on current literature and events. Their favourites of course were Robbie Burns and Stevenson, the Scotch being intensely patriotic, a sentiment seldom found among the English except in moments of hysteria, and which is more properly designated jingoism.

The conversation turned on politics and Mr. Young maintained that the working man is not influenced at all by the newspapers, and the masses of political and other tracts, pamphlets, booklets etc. which are showered upon him with such assiduosity by a misguided aspirant for election.

“Voting with the working man” he went on “is a personal matter. He is by nature suspicious especially of his own judgement and looks for someone to lead him. He can, of course, only be led by someone whom he trusts and respects, and therefore nearly always votes as he is told to do by the Trade Union officials or someone else whose personality has laid hold of his imagination.”

I believe that there is a lot of truth in what Young said. We afterwards talked of music, a subject in which my host was particularly interested. He told me of a Scottish opera company which some Glasgow magnate had financed at considerable loss to tour the lowlands, and spoke with enthusiasm of Tristan and Isolde, and other of Wagners’ operas. Mrs. Young afterwards showed me to my bedroom, where a fire was blazing in the hearth, and insisted that I should have my breakfast brought up to me in the morning as I was tired. I did not get downstairs until nearly eleven oclock on the following morning, to find that Mr. Young had gone off on a curling expedition, and that I was left en tete a tete with Mrs. Young.

She is a type of woman that I have seldom met. Charmingly naïve and simple, tender hearted and generous. Capable, I should think, of great devotion, and utterly unspoiled. There is not a scrap of cynicism in her nature. But like most of her sex she nourished a number of unfulfilled aspirations. Her husband is considerably older than her, and although intelligent, is by nature somewhat prosaic. She had left the school room, to settle down to the routine of a middle class home in Paisley, and longed to explore the illusive nature of romance and sentiment. She looked on me with interest because I belonged to a world which she in her ignorance imagined to possess a monopoly of romance, not understanding that its people spent most of their time plucking the little roses of illusion.

At first we talked books, and the conversation was rather stilted and formal. Then I hazarded the remark that women were the hard hearted sex. I could see at once that this remark pained her, and realized how utterly inapplicable it was to her with her generous heart overflowing with kindness, and affection.

“How can you say that” she askedThe subject dropped but I could see that she was pondering deeply over what I had said, and that it hurt her.

.“Well” I replied, “I have always found it so, indeed I look upon it as a necessary corollary of their defensive position in life.”

“But you must have been awfully unfortunate in the women you have met” she went on with her picturesque Scotch lilt.

“Perhaps I have,” I replied, “But for every one woman prepared to make a fool of herself for the sake of a man, I think you will find ten men who from sheer softness of heart will do anything for a woman.”

“I never thought of it in that way” she replied “Why, I always thought that all the pity, and mercy and love in the world came from women.”

“I don’t think so” I replied, “Of course books say so but I think that is because most of them were written by men who invested women with ideal characteristics which they never possessed.”

“But I cannot think that” she answered “you hurt me dreadfully when you say such things of women.”

“I am sorry” I replied “and of course I may be wrong, and am still open to conviction. But I think that women are thought to be tender and merciful and loving and to have the souls of angels, just because they are beautiful and fragile and delicate to look upon, and that by way of compensation nature has given them hearts of stone.”

“What wonderful adventures you must have had” she went on after a little while.I was at a loss what to reply and said that she had her books of which she seemed fond.

"You must have seen a lot in your life. Here in Paisley we lead very quiet lives. We just get up and do the same things every day and go to bed again at night. Our lives are not very exciting.”

“But books are never the same as life.” She observed rather sadly.

“Reading books is not the same as living, although it makes you forget the routine of your life for a while.”

I had to leave at 3 o’clock to go to Alloa where I was booked to give a lecture. Mrs. Young had invited me to stay on for a few days, and to take part in a Robbie Burns saturnalia with her husband, but this was of course impossible. She was kindness itself, looked out my trains in the timetable, ordered me a cab, saw that my things were packed.

“You will be having a cup of tea before you go, won’t you” she saidI thanked her for her kindness and hospitality.

“Oh no thank you very much” I replied, “I will get some in Glasgow, it is too early for tea”“Are you sure, because we will be getting it in a minute if you want it.”

And later, “Shall I come to the station with you and show you the train”

“Please don’t give yourself the trouble”

“Are you sure, because I shall be delighted to come if you want me, and mind you keep yourself warm on the journey, and don’t go catching colds”

“No it’s you we have to thank Mr. Bartlett for giving us so much pleasure and for your splendid lecture.”

I caught the train to Glasgow, and went from the Central to the Queens Street station. I had about three quarters of an hour to wait before my train went on to Alloa, and was pacing the station platform when suddenly I heard a voice by my side saying

“Well I came to see you after all.”Beside me stood Mrs. Young, and on her arm she carried my rug which I had left behind.

“I thought you would be wanting it the nicht, and so I just ran to the station and took the next train to Glasgow and here I am.”I thanked her profusely but she replied

“Well dinna think quite so badly of women in the future” and waving me goodbye vanished in the direction of the street.

Early morning 7 February 1913

Flumps (Humps?) has come to me; for what hidden reason only the gods themselves know. I dreamed that she had survived Charlie and Mokoff, and that Lady G and I went to stay with her, arriving unexpectedly at some unknown house in a far mysterious country. I had not seen her for three years, since before death came into her home, and never have I seen such a change in any living persons face. All the life and happiness had gone out of it, and it was all yellow and pinched looking, while in her eyes was the pained half frightened, half loving look of an ill treated animal. Our eyes met, and so many memories awakened in our hearts that we both turned away choking down our emotion with difficulty.

I had been looking forward to seeing her, had such lots to tell – all my adventures at the war – but at the sight of so much unhappiness in one whom I had always known as the soul of laughter, I sat dumb and miserable, not daring to speak or to look up and meet her eyes.

Shortly afterwards I awoke. Further sleep was impossible, because Flumps seemed to haunt me. I have always scoffed at things psychic, but I am sure that tonight, Flumps has come to me from the spirit world. She has some message to give me, some warning to utter. Perhaps she wishes to tell me that soon I must join her and Mokoff and Charlie beyond the veil. Who can tell? Anyhow I feel her all around me in the room as I write, and once more I feel how much I miss her and long for the sound of her happy laughter, or the light of her little all-understanding eyes.

7 February 1913 Blackpool

The Gods have punished me by sending me to Blackpool. The ostensible motive of my journey was to deliver a lecture on the Balkan war as I saw it, at the Winter Gardens. In reality nemesis had sent me there to expiate an outraged sense of beauty.

I stayed at the Hotel Metropole. Only some twelve people gathered for dinner. There two angular spinster ladies, a plump young married woman trying hard to look a lady in unaccustomed finery, another respectable mother with a young daughter, in an excessively hobble skirt, and an exaggerated hat which hid most of her much bepowdered face with its scarlet lips. The girl looked like the veriest wanton, but I am convinced that both she and her mother thought that she was of the very latest chic.

There were men, two colourless individuals, and a European adventuress, in the autumn of her days, whom fading charms and deepening frowns had driven from the fashionable haunts of the continent to eke out a precarious living in the Gordon Hotels, where her aristocratic pretensions dazzled the plebeian souls of merchants and retired shopmen.

Dinner over I repaired to the Winter Palace. A gaudy, scintillating chamber of horrors.An endless succession of palm courts, restaurants, refreshment saloons, billiard saloons, smoking rooms, theatres, picture palaces, ball rooms and so on apparently ad infinitum. All vast, all tawdry, all glittering and horrible, like a nightmare of pleasure gone mad, or torture devised for an artist in hell.

At the entrance I was met by Manaton my manager, a sad faced man who introduced me to a pompous individual with a very red face, a hustling moustache, bulging cods eyes, and an apopletic neck. Upon his dimpled fleshy fingers sparkled several diamond rings.

Manaton had just explained to him that Ellis was unable to come and that I was to take his place. The fat chairman thereupon produced six closely covered sheets of typewritten matter, and announced that it was the speech that he proposed to deliver when introducing me. Manaton gazed at him for a moment with surprised constraint and then said much to my embarrassment:”‘Ere what I wants to know his whether you I going to give the lecture, or his it Mr Bartlett”.

The fat chairman had evidently read through my brother’s syllabus, and had written a copious essay upon it. This of course had to be cut short, and he finally consented, not without chagrin, to confine himself to a few introductory remarks.

The great gilded hall was but scantily filled when the chairman and I took our stand upon the platform. His flesh was visibly palpitating with nervousness and his very first words betrayed the fact that he was illiterate:

“Ladies hand gentlemen”, he began, “Mr Hellis Bartlett”, then he cleared his throat vigorously,This so much shocked the only two old ladies in the stalls that they got up ostentatiously and left the building. He had meant to say co-correspondent of the Daily Telegraph but his nervousness had led him to refer to me as though I was a sort of professional co-respondant.

“Mr. Hellis Bartlett, is hunable to come ere tonight, he as gone back to the war”, more throat clearing,

“But is brother what accompanied im as to-to-to-to” he was seized with a fit of nervous stammering, which ended in: ”as co-respondent of the Daily Telegraph.”

After the lecture the chairman entertained me to a supper with champagne, in one of the gilded rooms of the Winter Gardens. He was full of praise of Blackpool saying that even Americans admitted that they couldn’t teach Blackpool anything, and then dilating on the wonders of the Tower and the Aquarium. He became confiding under the influence of much champagne, telling me that he had started life as an acrobat in a circus. I remarked that he had done pretty well since, as he was evidently a man of great possessions.

“Yes,” he replied, “But I often regret having left the circus. Look at Harry Lauder,” he went on “he’s making £20,000 a year. There’s nothing he did what I couldn’t do, and I could dance better than he could, because I ad been well taught but there wasn’t the money in it in my time. I was at the top of my profession and only earning £10 a week.”He appeared to have a personal grudge against Harry Lauder, but I doubted whether his own estimate of his talents was justified. He afterwards conducted me round the principal night resort of the town which consisted of an endless succession of saloons and bars, introducing me from time to time to flashy young men.